Totto Yama

100 Legacy Dr #110-107, Plano, TX 75023

Google: 3.7 Stars (68 Reviews)

Habibi-san’s rating:

I have gotten embarrassingly good at Excel. Thanks primarily to a few offshore YouTubers, I have become proficient in making reliable and consistent Excel models, akin to serving lightly seasoned entrées at Ruth’s Chris. Out of every Excel user in the world, I bet I could go toe-to-toe with 80% of them (please do not make me prove this). To put this in basketball terms, I could probably walk on to the UChicago Division III team. To put this in Michelin-recognized terms, I wouldn’t even sniff a Bib-Gourmand distinction. However, I never asked to become proficient in Bill Gates’ evil brainchild. Does an American inmate ask to become proficient in keeping highways litter-free? Just because you can do something doesn’t mean you should.

I will warn that this blog is brimming with lowbrow, surface level existentialism (Dostoevsky fans look away and return to your self-inflicted misery). It is another generic shout into the corporate abyss, albeit a financially healthy alternative to buying a sailboat in twenty years. Visiting Japan accelerated my path to an early-life crisis. Yes, the lifeless husks in fitted suits that parade around Tokyo are a constant indictment on the country’s corporate culture. However, the food culture tells a different story.

Independently owned, high quality restaurants are spread across Japan like Dollar Generals across Texas. These Japanese restaurants establish themselves as neighborhood cornerstones, rack up a cumulative rating over 3.5 on Tabelog, and start ramping their hours down. In Japan, food quality to hours of operation is inversely proportional. A highly rated curry shop may be open from 11:30 – 2:00 PM for lunch and 5:00 – 9:00 PM for dinner. Sometimes that curry shop is closed randomly on a Tuesday because the owner/server/chef is catching a matinee (or taking a much needed break; the point is I’m starving).

I am sure at some point that everyone’s YouTube algorithm has pushed a clickbait video from “Eater” or some Vice subsidiary titled “Japanese chef has been making gyoza the same way for 50 years…” To be fair to Vice, I am the clickbait’s main demographic, a tasteless critic who chose a Japanese culture obsession over a vested interest in the Civil War. Mastery of niche trades or techniques is ubiquitous in Japan, yet it intrigued me enough to have a mild existential break. It doesn’t feel fair. How can someone find their vocation so easily? I can guarantee my mother did not force life into my lungs so I can budget within a 5% confidence interval.

Five-year old Habibi-san thought his vocation was to play with puppies all day and magically mend the wing of a pirate’s shoulder parrot. However, I probably would have made a poor excuse for a veterinarian given I tried to kill God when my childhood dog passed. Somewhere along that path of very early career planning, I developed a clear love for writing. The imaginary lifestyle of a successful author was a big selling point in my teens. “I will write one book a year and work four hours a day, no problem.” If I know anything from watching Brandon Sanderson’s BYU lectures, I was completely full of shit. Just because you should do something doesn’t mean you can. Maybe I have the same proficiency for writing that I do for Excel (granted, writing quality is subjective and EBITDA calculations are not).

This is all a tangential way of saying that I do not fault successful Japanese chefs for having such limited hours of operation and relatively expensive prices: supply and demand, baby. However, before 11:00 AM, your choices are typically the nearest Lawsons, Doutor, or Matsuya, and I am a huge proponent of the breakfast beef bowl (gyudon). Whether you walk into any major fast food chain in Japan, most commonly Matsuya or Sukiya, gyudon is delicious and consistent.

It is like one of my reused macro-embedded Excel spreadsheets served within two minutes of ordering and doused in shredded cheese and scallions. Much like my work life, gyudon is neither fancy nor healthy, but it is satisfactory and sometimes the only option available. There are multiple ways to eat gyudon, but the only wrong way is ordering it without a raw or soft boiled egg. I ordered two on my first trip just to be safe:

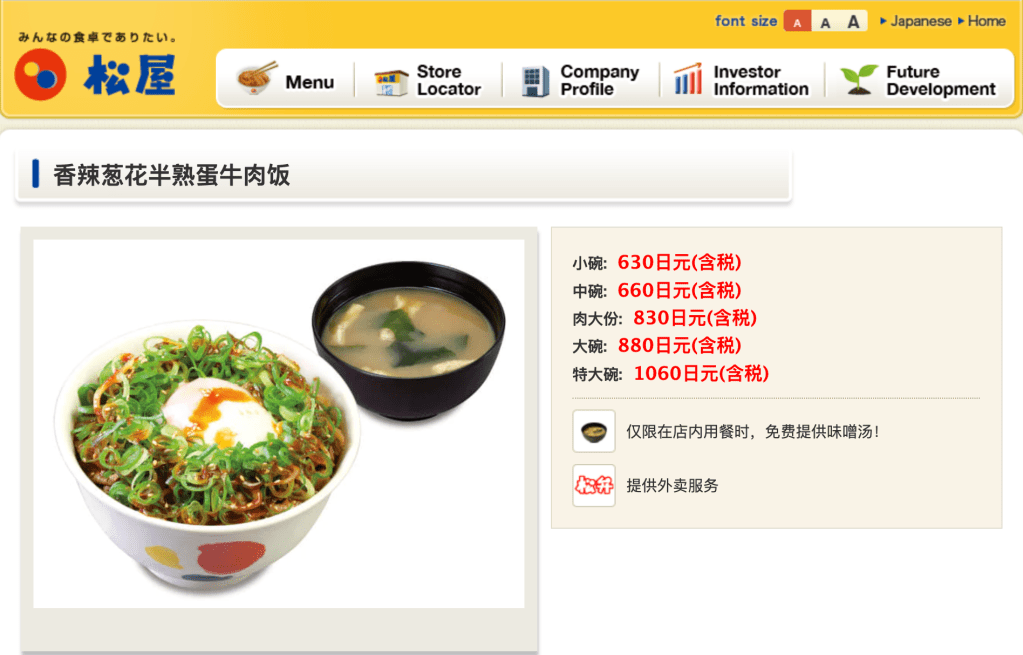

Having just been simmered in a bath of dashi stock, soy sauce, sugar, and mirin (syrupy rice wine), the thin slices of beef were juicy and sweet. These beef bowl chains are open 24 hours a day and their gyudon somehow tastes even better between the hours of 2 and 8 AM. Each seat boasts its own variety pack of yakiniku sauces, Japanese seven spice, pickled radish, and creamy dressing for the under ordered side salad. The regular size beef bowl set with miso soup I ordered was 660 yen or $4.56 USD. The beef alone from Mitsuwa or H Mart in the U.S. would cost more than that.

Out of everything I ate in Japan, I have thought about this beef bowl the most. The simplicity, efficiency, and quality of Matsuya has locked me in an inescapable mental chokehold. To avoid psychological persecution from perfectionism, I have recently begun to visualize Japanese gyudon as a guiding life principle. Why master something in which I have no interest? Just because I can do something doesn’t mean I should. AKA, my level of Excel knowledge is right where it should be. I do not need to create the 14-course omakase equivalent of my corporate skills (which would be signing up for the next Microsoft Excel World Championship on ESPN Ocho).

I have the skillset I need already. Working in Dallas, Texas is already enough of an apathetic minefield to worry about adding Power BI proficiency to my analytical tool belt. If I want to become better at anything, I choose writing.

Someone tell the good folks at Totto Yama in the food court of Plano’s Mitsuwa to also have a mild existential break. While curry and sukiyaki make up the majority of their menu, one of their featured items is gyudon.

The beef marinade was steeped in an authentic combination of dashi, sake, mirin, soy sauce, and sugar that raised my spirits and glucose levels in tandem. However, the key to a successful gyudon is sauciness and tenderness. A noticeable lack of beef broth was drizzled over my rice and several slices of beef were overcooked and slightly chewy. Thin slices of beef from ribeye or chuck only need 2-3 minutes to cook and change color before Habibi-san has a semi-severe crash out. Scallions, cheese, pickled radishes, kewpie, soft-boiled eggs, seven spice, and yakiniku sauce were also sorely missing from the menu and tables. While not a gyudon specialty shop like Matsuya, Totto Yama could take a page out of the fast food chain’s book and add some purchasable toppings to their gyudon. They work in a grocery store for God’s sake.

Maybe kids nowadays would stop joking about “late stage capitalism” and “recession indicators” if everyone operated at an 8.4/10 efficiency like a Japanese gyudon chain. But, I won’t pretend like I have anything figured out. I cracked my raw egg too hard on the table at Sukiya during my last day in Shibuya and spilled my hopes and dreams of a perfect gyudon bite across the counter.

My wife silently laughing while locals looked at me with exasperated embarrassment probably spurred the existential crisis in the first place. Do yourself a favor, make homemade gyudon with all the fixings. Maybe it will inspire you to learn how to INDEX-MATCH or write the next great American novel.

Ma al salama (さようなら ),

Habibi-san

Leave a comment